The Richness of the Kantha Embroidery

Introduction

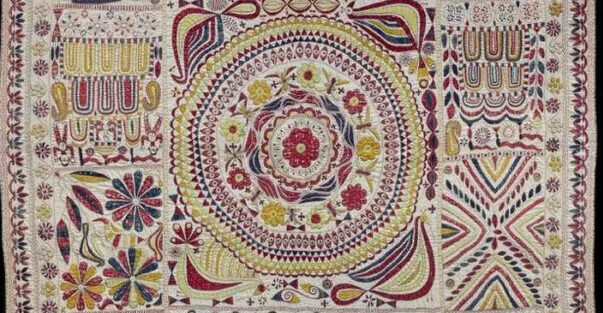

“Kantha means a patched cloth made of rags the embroideries called ‘kantha’ are stitched on rags” (Kramrisch, 1939, p.169). Katha, also pronounced as kheta, kaentha, is in reality an amalgamation of the factors that represent the identity of Bengal; “Apart from being a functional article, the kantha is also an example of folk art, particularly women’s art…. Folk art has always been composed of material most readily available. The area encompassing Bangladesh was, from earliest times, a cotton growing and weaving area. Thus, the material used was cotton textile…” (Zaman, 2012, p. 39). “Kanthas are an expression of the unique Anglo-Bengali culture that developed during the British occupation of Bengal that had begun in 1757” (Gillow & Barnard, 1991, p. 189). “The kantha made by the women of Bengal, “is a work of thrift, it is also an offering of love.” Kanthas were designed to be worn as wraps in winters or for protecting books, mirrors, combs and other valuables. They were used as pillow covers or folded as wallets. If very large, they were used as bed-spreads for honoured guests (Ward, 1954, p. 24).”

Source: Mayuri Bhattacharjee personal collection

With its base made up of “waste material” where old or discarded saris are “arranged, one on top of the other to the required thickness, with edges folded in and sewn together with common running stiches in which white thread covering the entire field to lend strength and durability. This is then filled in with fine quilling work by means of a white thread, while coloured threads drawn from the borders of the old saris are stitched along the border line and the surface is filled with different designs” Before the quilling process the process of tracing the design is accomplished, and the linen of the design remains unquilted and held together by the embroidery (Chattopdhyaya, 1964, p. 8). William E. Ward elaborates the symbolism that is attached with the kantha embroidery, where the lotus flower symbolises the universe and its creation. The other sacred symbols include leaf of Bodhi tree, peacock, tortoise, fish, elephant etc (Ward, 1954, p. 11).

Historical Perspective

Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya suggests, “Kantha is an example of a strange contradiction, for here is an object created at an endeavour at thrift by, transforming worn out textiles that would normally be thrown away, into objects of rare beauty and which have in course of time become legendary” (Zaman, 2012, p. 44).

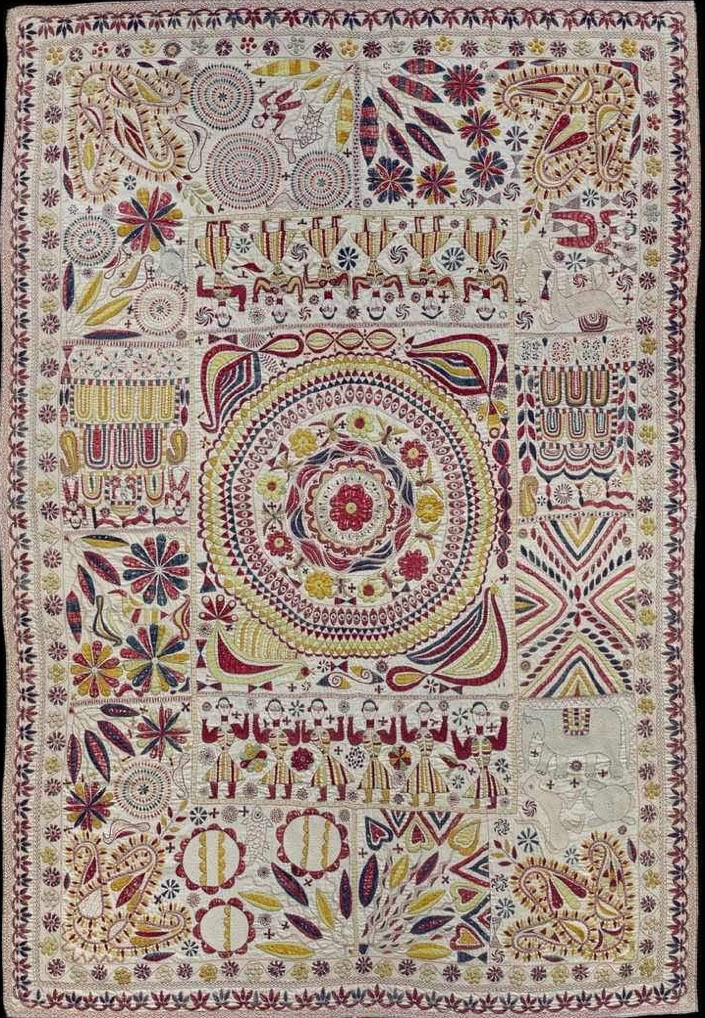

Source: Mayuri Bhattacharjee personal collection

Kantha quilling evolved as a leisure activity among the women of West Bengal and Bangladesh, in which they embroidered animal figures, villages scenery, mythological characters etc. on old and tattered cotton saris. “The layers would be prepared and held in position with weights placed at the corners. The four sides were basted/ tacked and the layers would be stitched through at regular intervals to hold them together. Close running stiches darned the pieces together so that the join between pieces was almost invisible.”

In the tradition style the thread used for doing the embroidery was taken out from the woven border and then was recycled. “The maker started in the middle of the piece, working outwards.” Initially the motifs created were drawn from memory, however, this practice is changed now, when almost all the motifs to be embroidered are firstly traced on the cloth (Srivastava, 2001, p. 40).

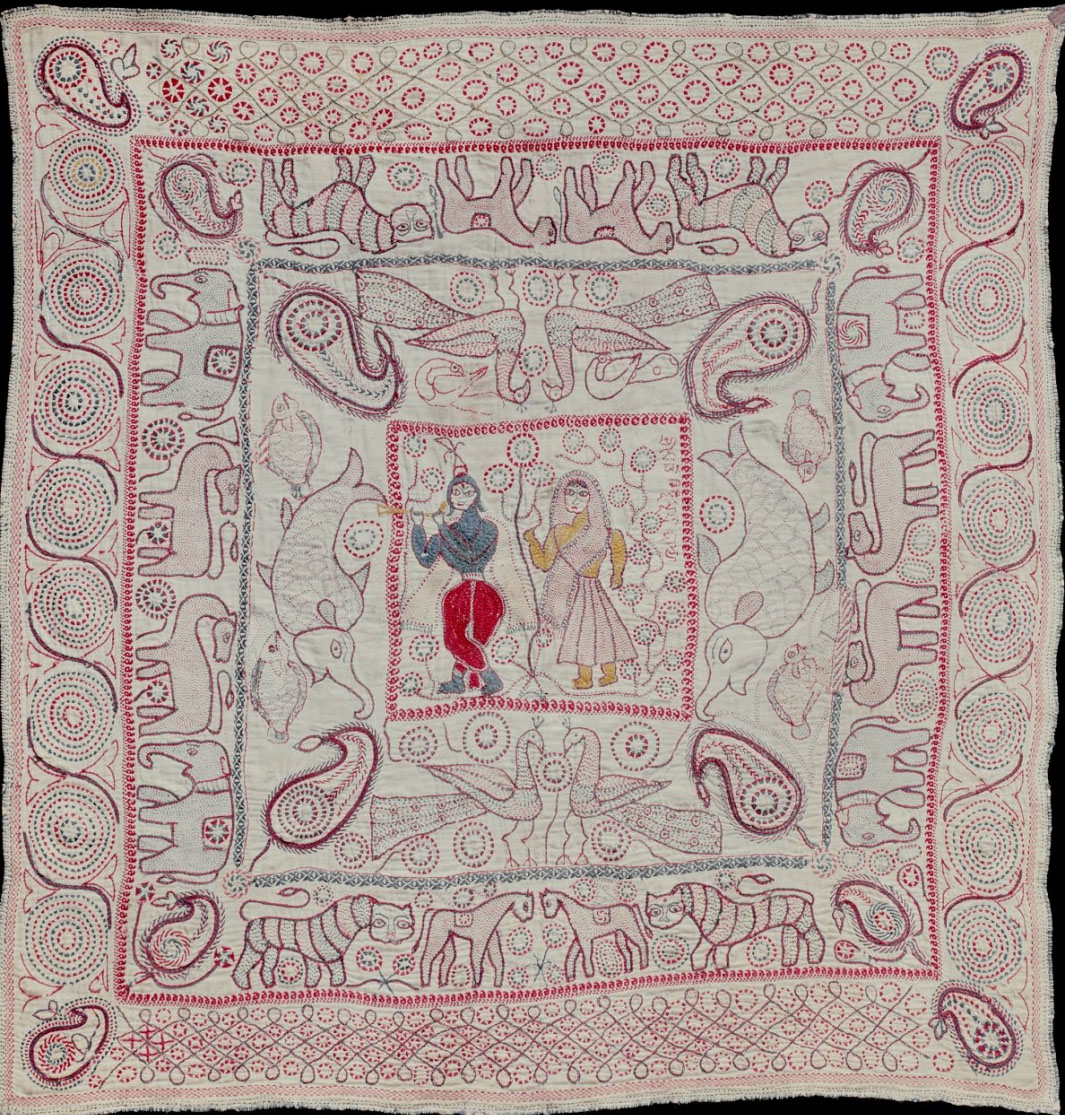

Source: Mayuri Bhattacharjee personal collection

The finesse and exquisiteness of the Indian embroidery tempted the Portuguese to commission quilts from India, mostly depicting both Indian and European motifs, which became known as the Indo-Portuguese quilts (Zaman, 2012, p. 44). There is a strong likelihood of kanthas being inspired by the sixteenth century Indo-Portuguese embroidered quilts of Satgaon by some, where different districts of Bengal evolved a distinct style of kantha embroidery. Rajshahi leharia quilts from Jessore, thick winter quilts and embroidered rumals from Faridpur (Gillow & Barnard, 1991, p. 188).

Tragically, around the end of first quarter of twentieth century, the tradition of making kathas made for “home consumption” died out. This was largely due to the rapid growth of industrialization and rapid changes in the rural lifestyle. East Bengal (now Bangladesh), was the main centre of katha weaving. “Here embroidered, quilted hangings are made with new cloth to some of the old designs,” and the purpose of these new kathas is export and tourist market (Gillow & Barnard, 1991, p. 173).

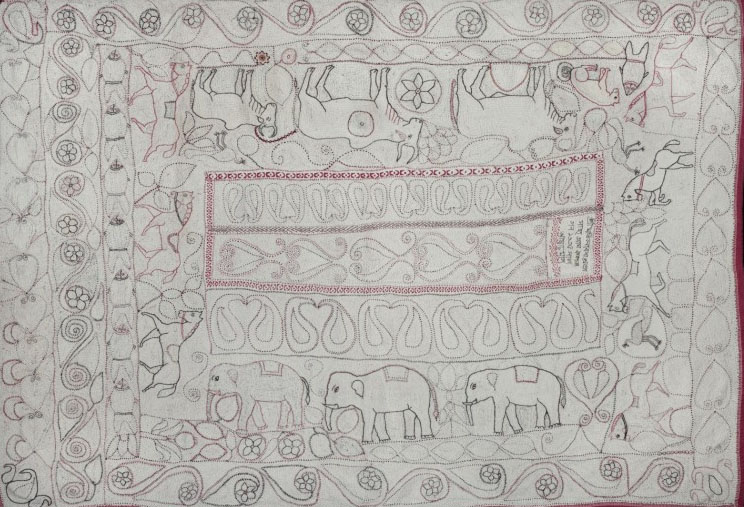

Source: Additya Mookherji personal collection

However, during the latter half of the twentieth century, the kantha embroidery gained prominence in Bengal, “a folk-art quilt made from old saris and dhotis, created in Bangladesh, West Bengal and parts of Bihar (where they were called sujani)” (Lynton, 1995, p. 49). The credit for reviving the kantha tradition goes to the Canadian aid workers, who took up this task to provide the rural women with a substantial source of income after the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971. Jamalpur district emerged out as a budding centre where “standardised light quilts and hangings are sewn to be sold by charity outlets within Bangladesh and abroad (Gillow & Barnard, 1991, p. 191).”

Source: BBC

From 1980s, the “kantha style running stich” was done by the rural women from the local parts of the State, where these designs are created by professional designers who provide the rural women with the “stencilled designs.” These embroideries are done on tasar and mulberry silk and often replicate the kantha designs from the ninetieth century (Lynton, 1995, p. 49).

Kantha Quilting

It is often seen that kantha quilts adorned with figurative motifs. “The quilter changes the colours of the quilting stiches to form images of people and animals and domestic and agricultural implements. Up to seven layers of old sari or dhoti (in Bengal woven using thin, light-permeable muslin) are quilted together to make up cold-weather quilts, eating cloths, purses or wraps for mirror or precious objects and cloths for religious rituals” (Gillow & Barnard, 1991, p. 187).

Source: BBC

Most common images made using the embroidery are that of a circus “strong men and acrobats,” depiction of famous figures from Bengali mythology, the most preferred one being that of witches or churails as “snuggle-toothed old crones.”

Source: BBC

Images from politics and literature also find their place, while some later examples include images of famous actress like Marilyn Monroe, World War II sailors. Yet another interesting addition happened while embroidering the Faridpur kanthas in the latter half of the twentieth century, when women who created these designs were also depicted in the cloth, “dressed in hybrid Anglo-Bengali costume with touched Edwardian English blouses combined with Bengali saris. Most preferred colours used in a kantha were black, red or green (Gillow & Barnard, 1991, p. 189).

Source: Desh Crafts

Over the passage of time, the style of making a kantha evolved drastically. Nowadays instead of using an old worn-out cloth, new piece of cloth is used for the embroidery, on which extremely fine embroidery is done, when at times can be confused with a woven pattern. While working on a silk sari embroidery is used whereas when it comes to quilts, white cotton is worked upon.

The Bihar quilts also known as sujani are used for making bed covers. “They use much the same stiches as the kantha pieces, but they have remained more naïve and closer to their human folk-art origins” (Srivastava, 2001, p. 40).

Kantha embroidered sari usually takes up to three months to get completed (Ellensa, 2007, p. 180).

Kantha and Bengal Embroideries in Literature and Folklore

The earliest reference of the Bengal embroideries goes back to 1516, by Duarte Barbarosa, who wrote, “They have beautiful quilts testers of beds finely worked and painted and quilted articles of dress.” In 1629, a Portuguese missionary, Sebastian Manrique, travelled to Bengal, his observations were, “Among the more important commodities dealt in by the Portuguese in Bengal are very rich back-stitched quilts, bed hangings, pavilions and other curious articles worked with hunting scenes which are made in these kingdoms.”

Source: Mala Bhattacharjee personal collection

However, the kantha lost its glory and significance in the eyes of the people during the British Raj, despite of the fact that women never stopped making it. Kantha is mentioned in various folklores and fairytales which are native to Bengal. However, there the kantha embroidery is associated with poverty. For instance, Mohammad Sayeedur talks about how Raja Gopichandra, in the 12th century, took up a kantha when he renounced worldly privileges and became an ascetic. The kantha tradition is also mentioned in the Baul songs.

Kazi Nazrul Islam employs kantha as a metaphor for a winter morning. “The land snuggles under a winter mist much as a man snuggles under a kantha” (Zaman, 2012, p. 52). However, the most famous reference of the Kantha embroidery is done by the celebrated Bangladeshi poet Jasimuddin in his poem Nakshi Kanthar Math, which was translated in English by Mary Milford as “The Field of the Embroidered Quilt” (Datta, 1988, p. 1805).

Quintessence of Kantha

The different types of kantha embroideries have different purposes. The thick quilted lep is worn in winters. Large and rectangular, Sarfin is used in ceremonies. Wide bordered rows depicting humans and animal figures with a lotus in the centre and tress adorning the corners along with squares, are the designs of a bayton which is used as wraps around valuables including books. Pillow covers are made with the oars, which consists of designs of trees, birds along with “a number of longitudinal border patterns and sometimes an extra decorative border round the edges.” Wraps like arshilates, which are designed with creepers, flowers and trees and are used to decorate and beautify mirrors and combs. For the purpose of covering a wallet, Durjani or Thalia are used, in which a square piece is adorned with a lotus in the centre and embroidery is done at the borders (Chattopadhyaya, 1964, p. 8).

Source: Philadelphia Museum

During various festivals and rituals Kantha used in “the fulfilment of vows and for each occasion has a special ritual design.” A hundred petalled lotus is made in the Mandala, in a Satadala Padma, different threads are used to create several concentric rings, “circumscribed by pots (the kalsas) or by conch shells, the shankhas.”

“Kanthas rarely adopted a narrative mode. They concurred themselves with images, each having its own reality, each equal to the other in terms of pictural value” In these designs each image created, instead of being part of a narrative was complete and independent in itself (Jain, p. 2002, 41).

Later, however, new images started emerging which included that of “Europeans playing cards, women seated on a Victorian chair posing as if playing a sitar, Raja Ravi Varma’s heroines, Jesus and his lambs, a European milkmaid holding freshly cut flowers, ears of wheat, Shiva cast in the image of Madonna, a European boy with his pet dog, holding a whistle” (Jain, p. 2002, 44).

Source: Philadelphia Museum

The Ashutosh Museum houses a rare kantha embroidery, in which the name of the woman who embroidered it, along with the name of the person responsible for creating the designs and the name of the person for whom it was made were inscribed (Das, 1992, p 115).

Stella Kramrisch and Kantha

Art Historian Stella Kramrisch, made unparalleled efforts along with Rabindranath Tagore in collecting kanthas from East and West Bengal. This rich collection of kanthas is now housed in the Philadelphia Museum of Art in the USA.

Conclusion

Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya beautifully writes, that kantha “presents vivid narratives of legends and heroic tales of the past and always serves to inspire those who use it and live with it” (Chattopadhyaya, 1964, p. 8). “Whether the kantha was a simple, utilitarian wrap, or a highly embroidered asan or sujni, it testified to the warmth and love a Bengali woman was capable of as much as to her perspective vision and artistic skills” (Zaman, 2012, p. 48).

Bibliography

Chattopadhyaya, K. (1964). Embroideries. Mumbai: Marg Publications.

Das, S. (1992). Fabric Art Heritage of India. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications

Datta, A. (1988). The Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature, Volume 2. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi.

Ellena, B. (2007). भारत सूत्र: India Sutra on the Magic Trail of Textiles. Haryana: Shubhi Publications.

Gillow, J. & Barnard, N. (1991). Indian Textiles. New York: Thames and Hudson.

Jain, J. (2002). Contemporary Indian Art. Mumbai: Marg Publications.

Kramrisch, S. (1939). Kantha. Journal of the Indian Society of Oriental Art 7.

Lynton, L. (1995). The Sari: Styles, Patters, History, Techniques. London: Thames and Hudson.

Srivastava, M. (2001). Embroidery Techniques from East and West: Texture and colour for quilters and embroiders. United States of America: Trafalgar Square Publishing.

Ward, E.W. (1954). Indian Painting and Folk Art, XVII Century—XX Century. United States of America: Cleveland Museum of Art.

Zaman, N. (2012). The Art of Kantha Embroidery. Bangladesh: The University Press Limited.