The Genesis of Temple Architecture in Ancient India

Indian mythology views the entire earth as a unified, interconnected temple, drawing a parallel with the idea of the human body, Purusha (Khanna 1997) . The temple has historically been central to the community’s socio-economic and cultural life, serving as a place of worship, administrative centre, marketplace, residence for Brahmins and artisans, educational institution, and custodian of artistic traditions. Local governance often operated through temple institutions, with state authorities directing rulers to levy taxes for the temple, highlighting state power. Temples also allowed landlords and wealthy merchants to exert their influence (Rajan 2019).

Tracing Continuity Between Indus and the Sutra Period

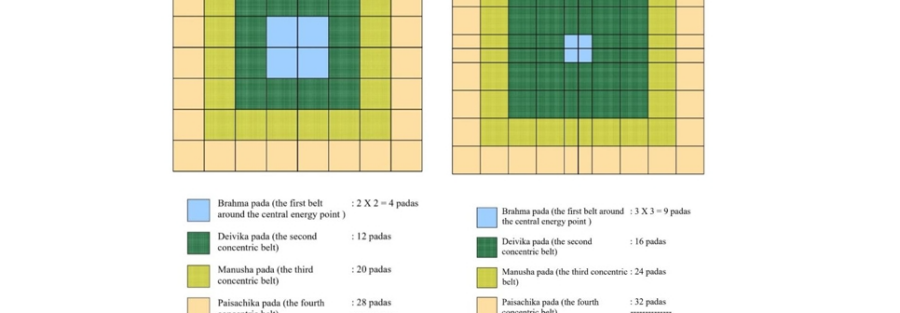

Archaeological findings from the Harappan period suggest a link to Vedic principles, particularly in Mohenjo-Daro, where a structure with a central courtyard and symmetrical rooms contains low brick platforms likely used for rituals. Evidence of fire altars in the courtyard which were later also found at Lothal (Kak 2005). The prominent urban centres of Ayodhya, Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro, and Lanka were constructed in accordance with the principles of Vaastu Shastra. (Pashmeena Vikramjeet Ghom n.d.) The urban planning of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro showcases advanced design principles. While it may be tempting to link these structures to Vaastu Shastra, this is historically inaccurate since Vaastu Shastra developed later. This does not directly connect them to the rituals in the Sūtra texts, but it highlights the cultural continuity between the Harappan civilization and the Sūtra period.

Figure 1. (i) Fire temple from Mohenjo-Daro; (ii) Fire-altar from Lothal. Source: (Kak 2005), Accessed on: 26.02.25

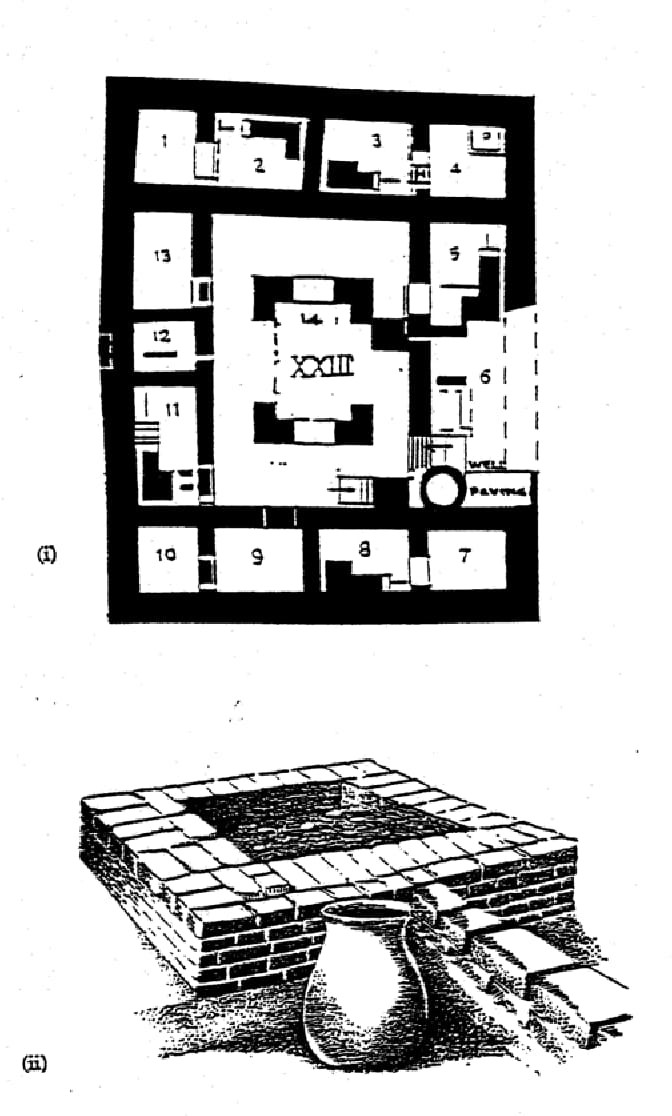

Concept of Vastu Purush Mandala

Vastu Shastra, a key part of the Vedas, is believed to have originated around four to five millennia ago, with its earliest manuscripts dating back to that time. The Earth as a living entity is central to Vastu Shastra, embodied by Vastu Purusha. The construction site is seen as his domain, called the Vastu Mandala, which serves as an architectural blueprint and is highly respected. His influence extends from the South-West (Pitrah) to the North-East (Isana). The Vastu Purush Mandala is viewed as a miniature universe, reflecting the principle of ‘यथा पिंडे तत् ब्रह्मांडे’ meaning “what exists in the microcosm also exists in the macrocosm.”

Figure2: Formation of Vaastu Purusha Mandala (Source: (Pashmeena Vikramjeet Ghom n.d.)) Accessed on: 26.02.25

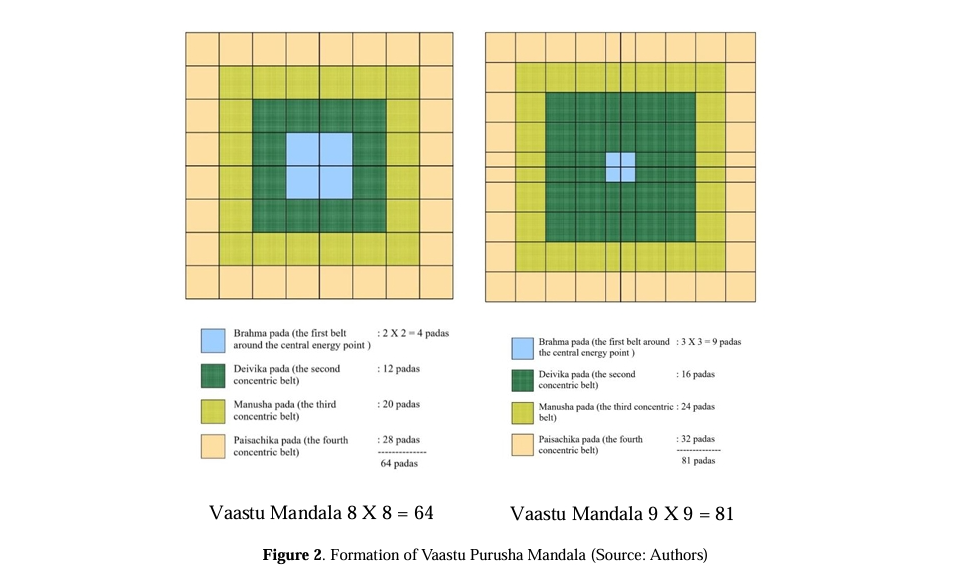

Caitya or Yaksacaityas

In 1930, Coomaraswamy published a significant essay on early Indian architecture, concentrating on Bodhighara construction and utilizing early texts and archaeological findings. He examined Yakṣas and investigated tree platforms dedicated to Yakṣas, Nᾶgas, and Caityas, becoming the first to mention the Jaina account of the caitya for Yakṣa Pūrṇabhadra. Ancient Yakṣa shrines featured gently sloping slabs beneath trees, akin to representations found at Bharhut and other locations. A relief from Mathura depicts a railing-free Vṛkṣacaitya, showcasing a Ṥilᾶpaṭa of footprints and a standing worshipper on one side, alongside a seated monk near a Sthᾶpana on the other, indicating that the shrine may be dedicated to a deceased Jaina monk Tίrthaṁkara.

Figure3. Medallion showing a Devayam ceiyam, "देवयम् चेयम्”, probably Jaina. Source: (Chandra 1967) Accessed on: 26.02.25

A lintel from the early Kuṣᾶṇa period in Mathura depicts a Saiva temple with a Siva Linga located beneath a tree, instead of a Śilᾶpaṭa. This structure is surrounded by a railing on all sides, but it does not have a roof.

Figure4. Mᾶlᾶdharas and Gandharvas worshipping Śiva Linga. Source: Wikimedia Commons, Accessed on: 26.02.25

The Mathura relief at the Boston Museum, first analyzed by Coomaraswamy, features a more advanced architectural design than the Mathura relief and the Aupapᾶtikasūtra’s description. It depicts a sacred tree surrounded by a columned structure with an arched entrance, identified by Coomaraswamy as a square Bodhighara with a corbelled roof, though the illustration does not clarify if it had walls. Evidences of other significant developments that influenced the later temple architecture are Jaggayyapeta, two storied shrines with gaṇḍa-prastha (wagon-shaped) roofs. Gop Temple (Gujarat), a later development with a pyramidal Śikhara which is linked to Kuṣᾶṇa prototypes.

Conclusion

The development of temple architecture in ancient India showcases a profound cultural continuity, intertwining religious beliefs, cosmology, and architectural techniques, while also playing a crucial role in shaping the socio-cultural landscape of Indian civilization.

References

Chandra, Pramod. 1967. “The Study of Indian Temple Architecture.” Varanasi: American Institute of Indian Studies.

Kak, Subhsh. 2005. “Early Indian Architecture and Art.”

Khanna, Ashok. 1997. Rhythm in Khajuraho.

Pashmeena Vikramjeet Ghom, Abraham George. n.d. “Scientific Rationality In Vaastu Purusha Mandala: A Case Study of Desh and Konkan Architecture.”

Rajan, K. Mavali. 2019. “Ritual Servants of the Temples: Gleaning from Epigraphic Records of the Chola Period.” Indian History Congress. 78-86.

Srivastava, Satya Prakash. 1943. “”Religion Under The Gupta Age.” (Inscriptions And Coins.):A Stusy in Culture.” Indian History Congress. Indian HIstory Congress. 116-124.

About the Author:

Author: Sauban Ahmad

Sauban Ahmad is a postgraduate student in the History of Art program at the Indian Institute of Heritage. He holds a degree in History from the University of Delhi. Additionally, he possesses knowledge of Sanskrit and Persian languages