The Elegance of a Paithani Saree

Introduction

Maharashtra is known for its variety of looms. The range of weaving varies from finest of cottons to the Saloos of Paithan, which are rich in brocade work. “The speciality lies in the design being woven without the assistance of a mechanical contrivance like a Jacquard or Jala. It uses multiple “Tillis” or spindles to produce the design. The design framework is linear and exquisite enamelled floral forms are woven on the background gold of the “Pallav or Border” (Marg, 1962, p. 8).

Location and History

Paithan is believed to be one of the oldest cities in the Deccan. This region has a reference in the Mahabharata, where it is said to be the capital of the Assakas, who had fought on the side of the Pandavas. In one of Ashoka’s inscription this region is mentioned by its ancient name, Pratisthan. An inscription at Pitalkhora, from the 2nd century B.C.E., makes a reference to the king and the wealthy merchants of Pratisthan. According to Ptolemy, this was the kingdom of Pabumayi II, and according to the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, this region was a significant trade centre (Dhamija, 1995 p. 61).

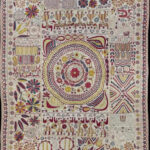

Source: Mayuri Bhattacharjee personal collection

Paithani weaving was patronised by the Peshwas. It was seen in many of the letters written by them, where they had placed an order of dhotis, dupattas, turbans etc. made of Paithani in different colours and varieties. There are documents which state their fondness for plain dhoti which is worked upon with a silver or golden thread, green turbans and dupattas with asavali or narali work in red, pink, orange and green. Paithani’s popularity was not only restricted to the Marathas, but spread to other royal patrons, such as the Nizams of Hyderabad, who’s family paid several visits to the Paithani weaving centres. New motifs on the border and pallu were introduced by the Nizam’s daughter in law Begum Nilofar (Desai, 2002, p. 313).

“Some of the oldest fragments of Paithani weave show a rather narrow elongated stylised buta, revealing Persian influence…. Later larger and complex butas were made, based on Persian prototypes commonly used in Mughal patkas and Kashmiri shawls” (Agrawal, 2003, p. 72).

Styles and Designs

“Quality silk and zari fabrics suitable for ceremonial occasions were produced at Paithan. The Ajanta floral motifs inspired the weavers.” However, they were not devoid of religious themes, such as the worship of Lord Krishna, because it is believed that numerous devotees of Krishna were associated with the weaving industry for a long a period of time. Dongerkery writes, “apparently, weaving was practised amongst a large section of people, irrespective of religion, but diminishing resources compelled the artisans to take to other forms of labour. Two to three scores of workers, however, stuck to their last and with the initiation of a programme for the revival of Paithani fabrics by the All-India Handicrafts Board, the languished craft shows signs of recoupment” (Dongerkery, 1955, p. 58).

These days the Ajanta style of the Paithani fabrics is evolved, where the floral and animal motif bears direct resemblance to the Ajanta Fresco motifs. “The Paithani style, especially in the borders, has been borrowed freely in the fabrics of the Deccan group. What is known as the pharaspeti and indori borders are but further developments of the paithani style” (Dongerkery, 1955, p. 59).

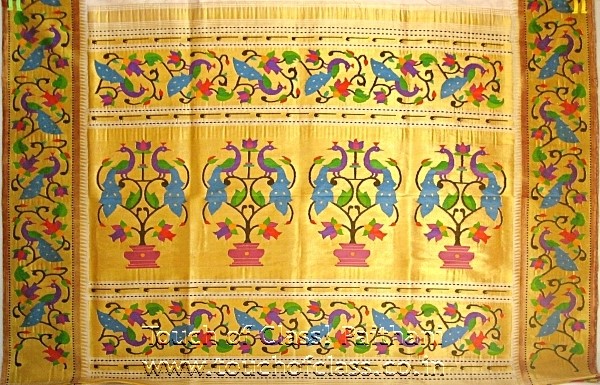

Image source: Touch of class Paithani and Utsavpedia

Paithani weaving

“A variety of techniques are used for weaving silk. The plain background is woven with tabby, twill or satin weave. Various methods for creating patterns on plain textiles are used such as brocade, tapestry etc.” (Agrawal, 2003, p. 58). Paithani weaves from India and the Sassanian textiles employ tapestry weaving in their fabrics. “In this weave, warp is stretched on the loom and weft threads of different colours are woven into it, not across the whole width of the warp, but each one only in the areas where its colour is required to form the pattern. Pattern formation depends on the capability of the weaver (as in embroidery); the most skilled weavers can produce patterns of any size and type, even with intricate details” (Agrawal, 2003, p. 58).

Image source: Kolour.in

Paithani weaving bears an absolute similarity with the weaving of a Banarasi sari. “Both keep the design underneath the silken warp strands and weave into it with the help of shuttles with great skill and precision” (Dongerkery, 1955, p. 59). Paithani saris are mostly made of silk and golden threads and are woven “on a rudimentary two treadle loom; the design is hand-woven by interlacing threads next to each other at the same level of the weft each time the colour changes. The weaver follows a paper pattern that has been placed under the threads of the warp.” When a golden thread is used for making a design on the silk cloth it is called a Zari brocade. When more gold is employed in the silk design and it gives the impression of being “set in gold,” the resulting fabric is known as a Minakari. It’s a family bases craft and the mastery of which is passed from generation to generation. “Minute minakari designs in the pallu using various colours is woven with the help of multiple spindles (tillies), which makes it a very laborious and complicated task.” (Ellena, 2007, p. 109).

“The borders are created with the interlocked-weft technique, either with coloured silk or zari. A wide band of supplement-warp zari (in a mat pattern) is woven upon the coloured silk border. In borders woven with zari ground, coloured silk patterns are added as a supplementary-weft ‘inlay’ against the zari, usually in the form of flowers or creeping vines. The endpiece has fine silk warp threads that are cut and retied to a different colour, as in the petni technique of Kanchipuram. The weft threads are only of zari, forming a ‘golden’ ground upon which angular, brightly coloured silk designs are woven in the interlocked-weft technique, producing a tapestry effect. These patterns usually consist of intertwining vines, branches, leaves and flowers, as well as parrots, peacocks and even horses and riders” (Lynton, 1995, p. 149).

Burhanpur Brocades

The Paithani tradition was carried forward in the Burhanpur brocades. Burhanpur province, was founded by Nasir Khan in 1400 C.E. during the Farukhi dynasty of Khandesh. It got its name from Sheikh Burhan-ud-din of Daulatabad. The Ain-i-iAkbari, refers to Burhanpur as “a large city with many gardens, inhabited by people of all nations and abounding with handicraftsmen.” The Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri states that Burhanpur was well known for its weaved muslins, silks and gold brocades. “The turbans, feta (sashes), saris and dupattas, with a pattern format somewhat similar to those of Paithan, were made here, i.e. the plain fine fabric background had narrow gold borders and pallu decorated with floral motifs, with a Persian influence” (Agrawal, 2003, p. 72).

The Paithani pallus “were woven with a weft of gold threads with patterns worked in silk with the interlocked tapestry techniques. This was exactly a technique of the Deccan and extended up to Chanderi. The older examples of the pattern carry; besides the pallu, borders are also woven with paithani technique. The saris were made in cotton and were nine yards long, worn in the sakacha or Maharashtrian style” (Dhamija & Jain, 1989, p. 154).

Source: Desh Crafts

Draping a Paithani

A typical Maharashtrian bridal sari is a green Paithani, which employs zari weaving on a pure cotton or silk. Geeta Khanna writes, “The colour green stands for fertility and is considered auspicious for a bride.” The wedding sari is usually worn in a Kaashta or Lavani style, which in turn find their origins in the draping style of a male dhoti. “This drape affords the wearer comfort of movement and was fashioned to allow women easy manoeuvring for their daily chores. Today it is also the drape for the Lavani dance” (Khanna, 2016, p. 77).

Post Independence

“When India became independent in 1947 and the programme for the revival of the traditional crafts was initiated by Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay in 1958, the only centre weaving this technique was Paithan and the technique became identified with this place. The weaver was commissioned to weave some traditional silk saris with a gold patti matt border and Paithani pallu. More intricate patterns were, however, revived by the All-India Handicrafts Board at their centre in Kothokotta, Andhra Pradesh. The Government of Maharashtra then revived the technique at Yeola. Centres such as Yeola, Wanaparti, Gadwal and Hyderabad did not weave borders with the tapestry technique but wove rich gold patti matt borders with the saris. It is possible, though, that in the past Paithan could have woven borders with elaborate patterns as was the case with the old Chanderi saris. The Technique and patterns imitated in the brocaded Asavali saris of Ahmedabad and Surat, as well as in Armoor in Andhra Pradesh, indicate the high value placed on Paithani weaves. The master weavers of Paithan, who at present work in Hyderabad with Suriya Hasan reviving some of the old patterns, claim that the gold thread produced in Paithan was the finest and richest. The weavers prided themselves on producing woven gold which was so translucent that it reflected the face of the weaver. However, by the end of the first quarter of the century they had begun to prepare such elaborate patterns, taken from Ajanta Caves, that the cost became prohibitive and the market died out. In the last thirty years, however, the demand for intricately designed, elaborately worked saris based on old patterns has grown. Many women in India now want to possess a Paithani sari in their collection. Once again old centres, except for Chanderi, are producing pallus and borders with intricate patterns now known as Paithani weaves” (Dhamija, 1995, p. 67).

“Wanaparti and Hyderabad also had a few weavers knowledgeable in the Paithani technique. Molkalmuru in Karnataka used the Paithani technique till the fifties but with a different style of motifs.” According to Jasleen Dhamija, this technique was “highly prised since a number of centres like Armoor, Gadwal and even Surat and Ahmedabad imitated the pallus during the beginning of the century” (Dhamija & Jain, p. 154).

Legacy Preserved

Jasleen Dhamija writes, “The older saris of Yeola and Gadwal have not survived, but imitations of the saris woven by other popular centres indicate that there must have been a great deal of stylistic variation. The Asavali saris imitated the curving border of parrots, flowers and leaves. Armoori saris had a rich gold pallu with a four-sided border in silk and kalgas in silver thread in the centre of the pallu, to create a Ganga-Jamuna effect. It also had a repeat of the kalga pattern above the gold pallu. This shows that a number of variations did exist, which have been preserved in the imitations” (Dhamija, 1995, p. 77).

Conclusion

“The Paithani weave is subtle yet rich. It is known for its closely woven golden fabric, which shines like a mirror. This is its distinguishing mark. In the shimmering gold background, various patterns (of butas, the tree of life, stylised birds, curving floral borders, and so forth, worked in red, green, purple and pink) glow like jewels” (Agrawal, 2003, p. 72).

About the Author:

Mrinalini Pandey is a Consulting Editor at Manjul Publishing House. Mrinalini, a Postgraduate in History, has given one of her Research Papers at the famous Cambridge University. She attended Oxford University and took a brief course in Anglo-Saxon History. She has translated Erich Segal’s Love Story into Hindi, and her most recent translation of Roald Dahl’s Matilda is now in print. One of her papers was just featured in the Oxford Middle East Review.

References

Agrawal, Y. (2003). Silk Brocades. New Delhi: Roli & Janssen BV.

Desai, K. (2002). Jewels on the Crescent: Masterpieces of the Chatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya. Mumbai: Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd.

Dhamija, J. (1995). Introduction: Woven Silks of India. Woven Splendours: Indian Silks. 46(3). Mumbai: Marg Publications.

Dhamija, J. & Jain, J. (1989). Woven Hand fabric of India. Ahmedabad: Mapin Publishing Pvt Ltd.

Dongerkery, Kamala S. (1955). The Indian Sari. New Delhi: All India Handicrafts Board.

Ellena, B. (2007). भारत सूत्र: India Sutra on the Magic Trail of Textiles. Haryana: Shubhi Publications.

Khanna, G. (2016). Style of India. New Delhi: Hachette India.

Lynton, L. (1995). The Sari: Styles, Patters, History, Techniques. London: Thames and Hudson.

Homage to Handlooms 15(4). Mumbai: Marg Publications. 1962.